Resiliency in Construction, Part I: The Case for Resiliency

Earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings do. This axiom captures the life-or-death importance of resiliency. In the fields of architecture, engineering and construction, resiliency is a term used to describe a building’s ability to hold up to the forces of a natural event or the wear and tear of time and the elements without suffering failure.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to resiliency. In some cases, it might mean disaster-proofing a building against the risk of total collapse; in others, it might mean updating aging infrastructure to withstand subtle threats over time such as climate change. These considerations are especially pertinent for education and healthcare facilities—spaces that not only house some of our most vulnerable citizens, but also serve as emergency response centers in the advent of calamity.

Building occupant safety during and after a natural disaster is of utmost importance, but it’s only one piece of the puzzle in the case for resiliency. On top of devastating injury and loss of life, structural failure in the wake of catastrophe has the potential to derail businesses and economies for many years to come. Financially speaking, it isn’t enough to ensure that a building is safe to exit in the aftermath of a disastrous event. The question becomes: Can the building remain operational?

When communities are full of non-resilient buildings that fall out of commission when disaster strikes, the economic consequences can reverberate through towns, cities, counties, states, regions and even entire countries, depending on the scale and severity. From this broader perspective, resiliency can be better understood as a community’s ability to bounce back.

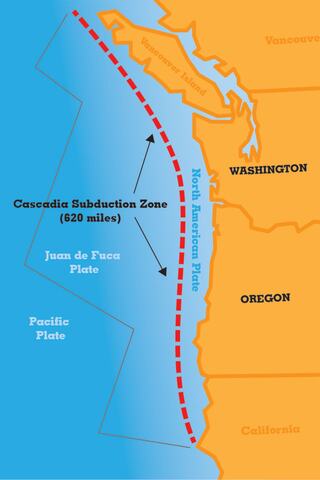

Thanks to a widely circulated article in the New Yorker back in 2015, a Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake and its threat to the Pacific Northwest’s ability to bounce back has loomed heavy on people’s minds. And while the potential for a devastating earthquake isn’t the region’s only threat to business continuity—there are also tsunamis, forest fires, landslides and flooding, to name a few—it’s certainly most top of mind.

Scientists have known about the 620-mile fault line that sits about 50 miles offshore from the Pacific coastline for decades, but conversations about earthquake response and preparation have only started gaining traction in recent years. This new sense of urgency is bolstered by the fact that Oregon and Washington’s most densely populated cities have high concentrations of unreinforced masonry (URM) structures.

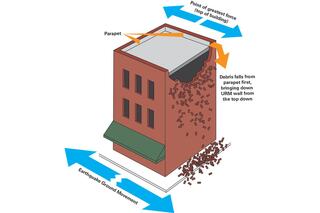

Deemed the most vulnerable to failure in the event of seismic shaking, URMs are at the center of an increasingly heated debate between building owners and local government officials. This tension stems from the fact that seismic retrofits, such as reinforcing parapet walls, strengthening the masonry skin and upgrading the structural lateral resistance systems, are costly. The situation is further muddled by the role of counties, states, the federal government, funding mechanisms, and building and occupancy codes.

Earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings do. This axiom captures the life-or-death importance of resiliency. In the fields of architecture, engineering and construction, resiliency is a term used to describe a building’s ability to hold up to the forces of a natural event or the wear and tear of time and the elements without suffering failure.

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to resiliency. In some cases, it might mean disaster-proofing a building against the risk of total collapse; in others, it might mean updating aging infrastructure to withstand subtle threats over time such as climate change. These considerations are especially pertinent for education and healthcare facilities—spaces that not only house some of our most vulnerable citizens, but also serve as emergency response centers in the advent of calamity.

Building occupant safety during and after a natural disaster is of utmost importance, but it’s only one piece of the puzzle in the case for resiliency. On top of devastating injury and loss of life, structural failure in the wake of catastrophe has the potential to derail businesses and economies for many years to come. Financially speaking, it isn’t enough to ensure that a building is safe to exit in the aftermath of a disastrous event. The question becomes: Can the building remain operational?

When communities are full of non-resilient buildings that fall out of commission when disaster strikes, the economic consequences can reverberate through towns, cities, counties, states, regions and even entire countries, depending on the scale and severity. From this broader perspective, resiliency can be better understood as a community’s ability to bounce back.

Thanks to a widely circulated article in the New Yorker back in 2015, a Cascadia Subduction Zone megaquake and its threat to the Pacific Northwest’s ability to bounce back has loomed heavy on people’s minds. And while the potential for a devastating earthquake isn’t the region’s only threat to business continuity—there are also tsunamis, forest fires, landslides and flooding, to name a few—it’s certainly most top of mind.

Scientists have known about the 620-mile fault line that sits about 50 miles offshore from the Pacific coastline for decades, but conversations about earthquake response and preparation have only started gaining traction in recent years. This new sense of urgency is bolstered by the fact that Oregon and Washington’s most densely populated cities have high concentrations of unreinforced masonry (URM) structures.

Deemed the most vulnerable to failure in the event of seismic shaking, URMs are at the center of an increasingly heated debate between building owners and local government officials. This tension stems from the fact that seismic retrofits, such as reinforcing parapet walls, strengthening the masonry skin and upgrading the structural lateral resistance systems, are costly. The situation is further muddled by the role of counties, states, the federal government, funding mechanisms, and building and occupancy codes.

Unreinforced masonry (URM) structure - Building Diagram

For building owners, this all begs the question: Who should be responsible for footing the bill for public safety? The answer is complicated, and cities like Seattle and Portland are still working to find meaningful solutions that don’t place the burden squarely in the domain of one group over another. In the meantime, however, the ball remains in the court of building and business owners.

As a commercial general contractor, Lewis has partnered with many building and business owners to construct resilient systems designed to protect against a range of structural threats. We’ve built in flood zones, tsunami inundation areas and places prone to forest fires. Further, we’ve retrofitted historical URMs and constructed all-new buildings that can withstand a 7.0–9.0 moment magnitude scale (MMS) seismic event.

The thought of what comes after a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake is enough to rattle anyone, but we shouldn’t allow that to deter us from adequate preparation. Having a plan is not only the difference between life and death, it’s also the difference between businesses that endure and shutter and communities that thrive and regress.

This is the first installment of a six-part series about resiliency in construction. Here, we discussed the case for resilience. Next, we’ll cover possibilities and a range of considerations for site-specific geological conditions. Finally, we’ll go deeper into the various systems that ensure a building’s ability to bounce back from a structural threat.

Project Executive Andrew Dykeman is an authority in sustainable construction and resilient systems. Andrew has managed some of Lewis’ most resilient and self-sustaining projects over the past two decades, including the Central Lincoln People’s Utility District, the Eugene Water and Electric Board Roosevelt campus, Elephant Lands and Polar Passage at the Oregon Zoo, and the Lane Community College Downtown Campus.