Population Heath: Why is Design-Build Fulfilling?

We asked a member from each major partner working on Population Health, an integrated design-build project for the University of Washington, how this project differs from previous ones, and more importantly, if this delivery method has affected their career fulfillment. What we learned was relatively simple; the collaboration, the innovation and the results are what keep each of these team members coming back each morning.

For any construction novices, integrated design-build is a subset of progressive design-build and incorporates all key project stakeholders from the start to optimize their ability to influence project outcomes. It is a method that has been around in one form or another for years, but recently grew in popularity after the delivery method was approved by Washington State legislature.

In a standard delivery method, each discipline independently works towards a project goal, which is usually different than the other disciplines also working on the project. In contrast, integrated design-build teams work together as a unified team under a common goal, using each partner’s expertise to deliver a project that is more cost effective, better meets the design intent and functions exactly how the end-user needs.

We’re going to let you in on a secret—design-build projects are equal parts challenging and rewarding and require complete buy-in from the client, the architect and the contractor—which is exactly what the University of Washington, Miller Hull, Lewis and KPFF, along with about a dozen other project stakeholders, have done to create a true design-build project with partnership as the driving force.

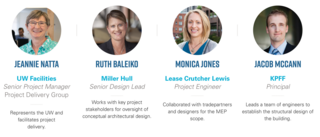

Meet Jeannie Natta, Ruth Baleiko, Monica Jones and Jacob McCann, four members of the Population Heath team, who played integral roles in making this idea a reality.

We asked a member from each major partner working on Population Health, an integrated design-build project for the University of Washington, how this project differs from previous ones, and more importantly, if this delivery method has affected their career fulfillment. What we learned was relatively simple; the collaboration, the innovation and the results are what keep each of these team members coming back each morning.

For any construction novices, integrated design-build is a subset of progressive design-build and incorporates all key project stakeholders from the start to optimize their ability to influence project outcomes. It is a method that has been around in one form or another for years, but recently grew in popularity after the delivery method was approved by Washington State legislature.

In a standard delivery method, each discipline independently works towards a project goal, which is usually different than the other disciplines also working on the project. In contrast, integrated design-build teams work together as a unified team under a common goal, using each partner’s expertise to deliver a project that is more cost effective, better meets the design intent and functions exactly how the end-user needs.

We’re going to let you in on a secret—design-build projects are equal parts challenging and rewarding and require complete buy-in from the client, the architect and the contractor—which is exactly what the University of Washington, Miller Hull, Lewis and KPFF, along with about a dozen other project stakeholders, have done to create a true design-build project with partnership as the driving force.

Meet Jeannie Natta, Ruth Baleiko, Monica Jones and Jacob McCann, four members of the Population Heath team, who played integral roles in making this idea a reality.

We interviewed each team member to understand the secret sauce that makes Population Health stand out for them. At the core of each interview, one thing stood out; Jeannie, Ruth, Monica, Jacob and the teams behind them are all experiencing a different kind of job fulfillment than ever before—intangibles like opportunities for connection, a deeper sense of purpose and feeling like their expertise is valuable.

Partnership Has a Purpose

Design-build is rewarding and challenging because it breaks down all the standard boundaries and forces each work group to work relationally rather than in a vacuum.

As you can imagine, at first each team member seemed hesitant to do away with the standard process and allow everyone to “see how the sausage gets made,” but the vulnerable moments are where true collaboration, camaraderie and innovation come to life. When you have the support of your team, you can push the limits, think outside the box and find groundbreaking solutions to common design and construction challenges. As an individual, you feel fulfilled because you are growing, becoming better at your job and feeling a sense of purpose.

“It’s a very safe place to be, and the most rewarding thing about work is always the people. Right?” said Jacob McCann. “When you can get to a point where you’re feeling like you’re going to work with your family, that’s pretty awesome.”

As with any group working that closely, there is healthy tension as well. As partners who often approach projects with different mindsets, working together to this extent means overlap, opposing ideas and strain. It forced each person to think outside the standard siloed approach and usual boundaries for what is possible, allowing the team to deliver a seamless project that is perfectly suited to the UW’s needs.

“It feels like the difference between playing Monopoly or Settlers of Catan. In Settlers of Catan, if we work together, we can all win. In Monopoly, the goal is for one person to get all the money and all the property. Someone else has to go bankrupt for someone else to win.”

— Jeannie Natta

Putting Expertise to Work

In this industry there are usually several iterations of ideas that are passed back and forth from design through execution. Often, an element designed by the architect at the beginning of the project and the element that is installed in the building can look, function and feel very different.

“As a profession there has been a distance between the designer and contractor. I think this method is helping us close the gap and realize we all bring a critical piece of the puzzle. We all need each other, and we all make the collective work better.” Baleiko said.

Ruth Baleiko leads a Population Health Big Room session at Miller Hull

One of the benefits of a design-build format like Population Health is that the designers, engineers and tradepartners that will install the work are all sitting next t one another and are working toward the same end goal.

The project team didn’t have to pass the plans back and forth to juggle constructability, design intent and budget. While redesigns happened, they were minimal and real-time, with the rest of the team actively participating. Since the entire team continually vets design ideas and works under a common goal, the design put in place is on budget, buildable and fits the client’s design intent.

“It doesn’t really matter what organization you’re with, you are able to talk about the project and the design components equally and I think that’s really transformative because it means that each group is equally invested in every project element.” Baleiko said. “As design lead, it makes me feel so much more confident because I know the product that we will deliver is going to be right.”

Letting Trust and Respect Drive Success

Like many others, this team is loaded with talented, eager and enthusiastic construction professionals, designers and tradepartners who each bring a unique outlook and expertise to the table.

“My favorite part of my day is finding a challenge and working through the gritty details with a person who is an actual expert to find the best solution, not just the easiest one,” said Monica Jones. “Where else is that possible in this industry?”

The differentiator here is that this design-build team is set up in a way that facilitates each person’s expertise and pairs them with a peer working on a congruent scope. Each person has direct access to everything they need to do their job effectively.

Key stakeholders on the Population Health team meet at Miller Hull.

“I am constantly surrounded by experts here, so any time I run into a challenge I can get access to the answers immediately. Since we are all working in the same space, literally, we get better answers and have an immediate feedback loop,” Jones said.

For engineers and designers who are still early in their career, this working style provides an on-the-job learning environment where they can partner with someone from another discipline to get a better understanding of how they work and what they need from one another.

“When young engineers get to sit next to the person who will build their scope and can describe how they’re going to do it, it helps shape how they’re going to draw their details and put their drawings together. It makes us all better at our job,” McCann said.

However, others, like Jeannie, Ruth and Lewis Project Manager Joe Nielsen, had to learn to give up some of their control and let the expertise on their teams drive the work.

“In some ways I feel like I have more ownership. I have a seat at the table and get to provide more insight at different areas than ever before. In other ways, I had to let go of the reins a little bit,” Natta said. “Both sides have pushed me to grow. I know that I have become a better leader because I have a better understanding of what each group needs from me,” she said.

Two carpenters onsite at Population Health.

Career fulfillment can take many different forms and mean different things to each person, and often, it goes beyond the number on your paycheck and the title on your business card. While those things can be important, ultimately, they are not the driver that keeps you excited to come to work each day.

While everyone has a different experience at Population Health, one thing is certain: the elements that make design-build unique, innovative and successful are the same elements that help these team members build meaningful relationships and go home feeling challenged, empowered and eager to take on the next project.

“It’s hard to imagine it being much more successful than this. It’s been pretty amazing to be a part of,” McCann said.

Luckily for them, the job fulfillment has just begun, because the team is already gearing up for their next opportunity: Health Sciences Education, a 100,000-square-foot facility for health education on the University of Washington campus.